This guide has been a collaborative effort, including text bodies from 20 authors, photo illustrations from 16 contributors, and countless hours of work by three co-editors. It took more than two years from the conceptualization of this guide to the finished product. Special thanks to the Southern Regional Small Fruit Consortium, whose financial contributions helped tremendously to finalize this guide.

We decided to structure this guide into four chapters. The first chapter serves as an introduction to strawberry production in the Southeast and includes a “Quick List” for those who are new to strawberry production. Chapter 2, “Cultivars, Marketing, and Economics,” focuses on currently available strawberry cultivars (varieties) as well as sections on general marketing and the economics of strawberry production in annual hill plasticulture in the Southeastern United States. Chapter 3, “Annual Hill Strawberry Production and Management,” will then take a deep dive into the nuts and bolts of what it takes to produce strawberries here in the Southeast. The final chapter, “Additional Considerations,” covers cropping, high tunnel production, and food safety. More information, including a complete enterprise budget for a u-pick operation, can be found in the Appendix at the end of this guide.

It is my sincere hope this guide will serve as a comprehensive source of information for growers and agents alike, and at the same time will be an enjoyable read.

Sincerely,

Dr. Mark Hoffmann (editor in chief)

Associate Professor, North Carolina State University.

Annual hill strawberry plasticulture was developed in conjunction with Methyl Bromide soil fumigation for the California strawberry industry in the 1950s. Adaptation of strawberry plasticulture in the Southeast was first reported in the early 1960s (Figure 1-1).

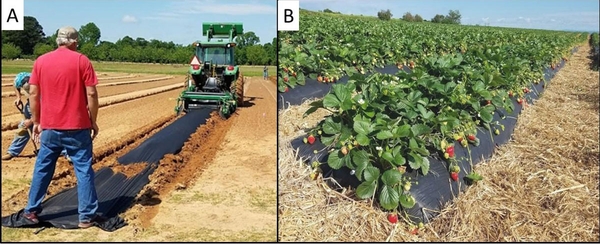

Plasticulture became more widely adopted in the Southeast from the 1970s through the 1990s (Poling 1987). Strawberry plasticulture is an annual hill cultural system that provides significant production and market benefits over the bare-ground matted-row system. Today it is the predominant strawberry production system for the $50+ million strawberry industry in the southeastern US. Annual hill plasticulture has the advantage of providing higher strawberry yields and better disease control compared to matted-row strawberry cultivation (Figure 1-2). In annual hill plasticulture, a grower plants new strawberry transplants (plug plants, bare roots, or cut-offs) into a raised bed on an annual basis.

In an annual hill strawberry plasticulture production system, a grower can plan to harvest a crop within seven to eight months of planting compared with 12 months in a matted-row system (Figure 1-2). The picking season for a strawberry plasticulture system is generally two weeks earlier than matted row and will last four to eight weeks (depending on the region), using short-day cultivars. Plasticulture allows for uniform plant stands every year (unaffected by summer disease, drought, or weed competition), larger berries, and easier picking with less labor. Disease (for example, gray mold, Botrytis cinerea) can be more easily controlled compared to a matted-row system. All these factors contribute to much higher marketable yields in annual hill strawberry plasticulture systems compared to matted-row systems. The plasticulture beds also allow growers to take advantage of drip irrigation for more efficient water usage, and the same drip irrigation system can also be used to feed the crop (called fertigation).

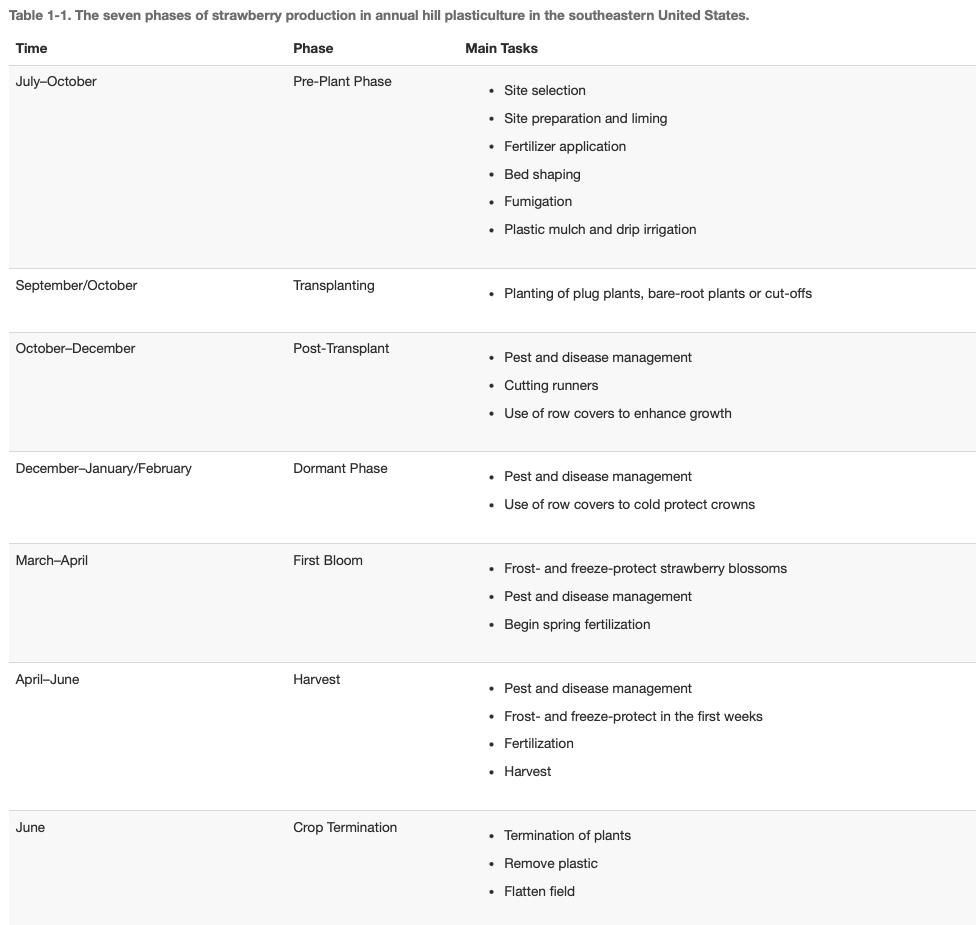

The annual cycle of strawberry plasticulture production can be summarized in seven steps, from pre-plant preparations (Step 1) to crop termination (Step 7) (Table 1-1).

The genus Fragaria (strawberry) belongs to the family of Rosaceae. Currently, 24 distinct wild strawberry species can be found worldwide (DiMeglio et al. 2014). The cultivated strawberry plant (garden strawberry) Fragaria x ananassa is a result of hybridization between F. chiloensis and F. virginiana, originating in Europe during the 18th century. Commercial strawberry cultivars are octoploids, which have eight haploid sets of chromosomes in each cell, each carrying a set of similar genes. However, there is a wide diversity of strawberry types in wild strawberry species that are not used for cultivation, ranging from diploid strawberry species (F. vesca) to decaploid species (10 haploid sets of chromosomes: F. cascadensis). Fragaria chiloensis and Fragaria virginiana, the parents of the modern commercial strawberry plant, are both octoploids and native to South and North America, respectively (DiMeglio et al. 2014).

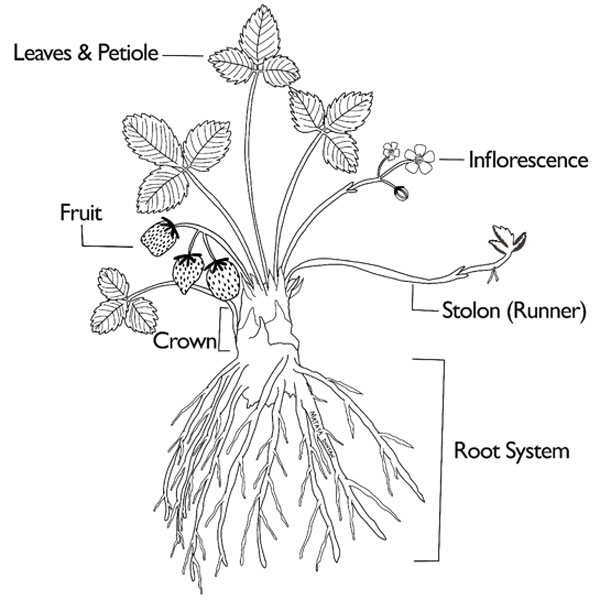

A strawberry plant can be classified into several distinct morphological structures: the crown, stolon (runner), leaves and petioles, root system, inflorescences, and fruit (Galletta and Himelrick 1990; Figure 1-3). The strawberry crown is a compressed stem-rosette, between 1 and 2 inches long. It is usually covered with overlapping leaf bases. The crown is comprised of auxiliary buds, responsible for the development of runners (stolons), branch crowns and inflorescences. Runners are elongated stems are comprised of several internodes and daughter plants. Daughter plants are new leaf rosettes, genetically identical to the mother plant and with the ability to develop into a complete strawberry plant (Galletta and Himelrick 1990; Hancock 1999).

The process of ”runnering” is used in strawberry nurseries to produce planting stock for strawberry growers and to fill in perennial matted-row strawberry production in home gardens. Strawberry plants have trifoliate leaves with three leaflets, attached to the main stem (petiole) (Figure 1-4). The strawberry root system usually consists of primary soil-penetrating roots, and secondary feeder and explorer roots. Between 50% and 90% of the root system of a mature strawberry plant can be found in the upper 6 to 8 inches of soil (Galletta and Himelrick 1990). In the Southeast, the root system usually composes between 40% and 80% of the overall strawberry plant between November and March. However, root systems only compose 10% to 20% of the overall dry weight of a strawberry plant between April and June (Fernandez et al. 2001).

The main stem of an inflorescence (flower stalk) is called a “peduncle.” Flowers (and later fruit) are held by a single stem, the “pedicel.” Biologically, the strawberry inflorescence is a “compound dichasial cyme.” It is a cluster of flowers from a common peduncle, developed by branching beneath the terminal flower (dichasium). This process continuous for two to four cycles of branching (compound), with some of the secondary branches missing and with pedicels of different length (cyme) (Galletta and Himelrick 1990).

Botanically, strawberry fruit are not berries. Berries develop from a single fertilized ovary and are characterized by fleshy walls. In a strawberry, however, the flesh of the fruit is produced by a swollen receptacle. The hard seed (“achenes”) on the surface are the true fruit of the strawberry plant. A strawberry is therefore a pseudocarp (or “false fruit”) since the actual fruit are the achenes on the surface of a swollen receptacle. The receptacle is the point at which the parts of the flower are attached. Several hundred pistils and a doubling ring of stamens are part of the self-fertile cultivated strawberry flower (Figure 1-5). Being self-fertile, strawberry flowers do not require cross pollination for fruit formation. It usually takes 20 to 30 days from pollen fertilization of a flower to form a ripe strawberry. Strawberry flowers are wind- and insect-pollinated and need several pollinator visits to be fully fertilized. Cool temperatures or the use of floating row-covers can reduce the amount of pollen transfer and pollinator activity, resulting in more misshapen fruit. This phenomenon varies widely by cultivars. Frost damage to the receptacle or parts of the receptacle can also lead to misshapen fruit.

In strawberries, flowering and runnering are controlled by different environmental signals, especially temperature, photoperiod, and nutrition. It is in the manipulation of environmental factors that a grower can improve yields and reduce runnering. How strawberry cultivars act in certain environmental conditions depends on their genetic make-up. Typically, strawberry cultivars are classified based on their flowering behavior. (1) Short-day (SD) or “June-bearing” cultivars develop flowers under shorter day-lengths (winter and spring) and bear fruit in early summer. They are a seasonal flowering type. Typical cultivars used in the Southeast are Chandler, Camarosa, Liz, Rocco, Ruby June, Sweet Charlie, Camino Real, and Fronteras. Long-day (LD) strawberry cultivars are less sensitive to day length and develop flowers over a longer season. Because of these features, the terms “day-neutral” or “ever-bearing” are often used interchangeably when referring to LD strawberry cultivars.

SD strawberry cultivars have the feature of one flush of flowering and fruiting in spring and early summer (Heide et al. 2013; Stewart and Folta 2010). Flowers in SD cultivars are initiated during colder temperatures and shorter photoperiods (day lengths), and runnering is induced during warm temperatures and longer photoperiods. LD cultivars are specifically bred for long-season production, especially in central and southern California (Bish et al. 2001; Neri et al. 2012; Castro et al. 2015; Arnade and Kuchler 2015). Flowering in LD cultivars can be initiated by longer day lengths and higher temperatures compared to SD cultivars. In the Southeast, the majority of strawberry production utilizes SD cultivars; however, the use of LD cultivars such as Albion or Monterey has become more popular in recent years but can be very challenging in the Southeastern climate.

Food production is a matter of national security in the US. The rapidly changing weather conditions present major challenges to current strawberry production systems nationwide. Changing climate already affects strawberry production in the Southeast. In 2023, heat domes affected not only growers who scrambled to protect their blossoms from heat stress. Wildfires in Canada widely affected strawberry nurseries that in return fell behind in delivering strawberry daughter plants to plug producers later in the season.

In the Southeast, spring frost events are more frequently followed by rain and early heat waves, and it has become more common for growers to frost-protect one night, only to either scramble to harvest before the rain or protect blossoms from heat damage. Recent winter deep freezes saw often temperatures drops from the mid-50s into the low teens or even single digits within less than 24 hours. Today, a strawberry grower in the Southeast places a lot of demand on a strawberry plant and cannot get around watching and interpreting weather forecasts very closely. North Carolina State University therefore provides timely weather alerts for the Southeast and Mid-Atlantic regions every winter and spring (from November through May). Growers are strongly encouraged to subscribe to the NC State Extension Strawberry Growers Information page to gain access to this free service.

By the end of the 21st century, a shift into warmer plant hardiness zones is projected for almost the entire Southeast (Carter et al. 2018). Under this scenario, strawberry cultivars with high chilling requirements or with the tendency to break bud at low growing degree days might become even more difficult to grow (Sweet Charlie is one example). It is possible that planting dates for cultivars such as Chandler will have to be pushed back to later dates to accommodate for increasing heat units in the fall. An increasing number of warmer days in late winter (January, February) may also shift the beginning of harvest weeks earlier than traditionally known. In 2023, for example, the first North Carolina field-grown strawberries were harvested as early as the first week of March, more than three weeks earlier than usual. This was due to a very warm late-winter season. Berries have had to be protected from frost and freeze events from February through late April of 2023. Such weather patterns will potentially be more common in the future, leading to an increased risk of spring frost damage and consequently to an increased labor demand for frost and freeze protection in the Southeast.

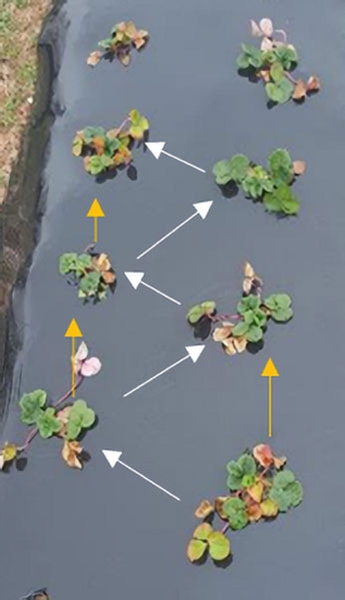

Tropical storms present additional real and direct threats to crops. The intensity of such weather events is expected to increase in the coming 30 years in the Southeast. Flooding in particular has been problematic for strawberry production in the past, as well as damage caused by heavy winds; both will continue to be problematic in the coming years. Detailed guidance on hurricane and tropical storm preparedness for strawberry growers can be found in Hoffmann et al. (2021). Even moderate rainfall in the spring frequently leads to fruit damage, and fall tropical storms have resulted in delayed planting and compromised planting material. Protected growing systems (Figure 1-11) can protect from weather issues but come with their own set of challenges and costs.

The selection and management of appropriate cultivars for different growing systems, as well as the availability of appropriate planting materials, are becoming more important in the Southeast as reactions to issues in supply chain and climate (Figure 1-12).

Strawberry growers in the Southeast have the fortune to select from a wide range of strawberry cultivars (often referred to as “varieties,” “varietals,” and “types”). However, such fortune can also become very overwhelming; growers in the Southeast need to consider many factors, often uniquely geared towards their farm and customer base, before making a decision on cultivar choice.

A successful strawberry operation in the Southeast serves a niche market in which the sales price is higher than the average US market price. Most, if not all, operations in the Southeast serve a direct-to-consumer customer base. Wholesale operations typically sell to grocery chains as “local produce” to achieve higher-than-usual shelf prices. This means growers have to select cultivars that appeal to their specific customer base. Flavor, yield, peak season, berry size, and appearance are some of the main characteristics that become more or less important, depending on the specific customer base. With increasing weather threats, a constant evaluation of a range of cultivars is highly recommended for any grower who wants to achieve a long-standing successful operation. For example, just because Chandler was the cultivar that appealed to your customers 10 year ago doesn’t mean it is still the best cultivar to grow today. A willingness to try and fail (on a small scale) and educating yourself about new and emerging cultivars is key to a long-standing success of a strawberry operation.

While there are currently more than 10 strawberry cultivars commercially used in the Southeast, the majority of those are SD (June-bearing) strawberry cultivars. LD (day-neutral, ever-bearing) cultivars are less common and mostly used in protected culture systems (such as a tunnel). The most dominant SD cultivars planted throughout the Southeast are Camarosa, Chandler, Ruby June and Fronteras. LD cultivars used in tunnel systems or greenhouse production are mostly Albion or Monterey. Other cultivars used in protected systems are Brilliance and Sensation, both strawberry cultivars from the University of Florida breeding program. The same is true for Sweet Charlie. University of Florida genetics are bred to flower early and under warmer conditions and are very difficult to grow in open-field plasticulture systems here in the Southeast. Newer cultivars on the horizon (as of 2023) are Rocco and Liz (from NC State’s breeding program), and Ashely Jay and Miss Joe (both from the Good Farms Breeding Program).

In the following section, we discuss cultivars that are generally found to be well adapted to environmental conditions across the Southeast. The breeding program that developed the cultivar is noted within parentheses after each cultivar name.

NCSU = North Carolina State University

LC = Lassen Canyon

UCD = University of California-Davis

UFL = University of Florida

The year the cultivar was released follows the breeding program institution. The states where each cultivar has been trialed or recommended are noted (AL = Alabama, AR = Arkansas, GA = Georgia, LA = Louisiana, MS = Mississippi, NC = North Carolina, SC = South Carolina, TN = Tennessee, VA = Virginia).

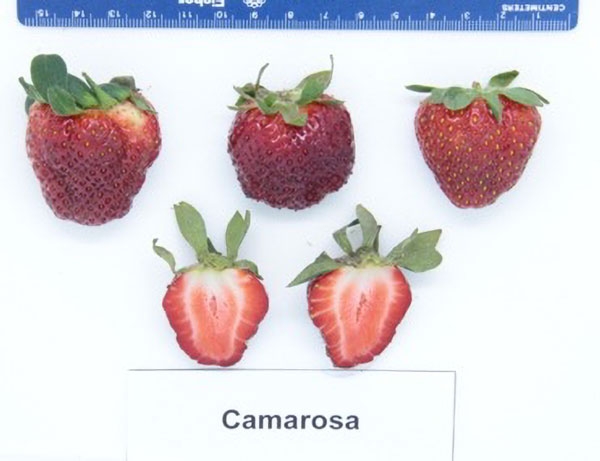

Mid-to-late season. Medium-size fruit, moderate steady yield through season (Figure 2-1). Good flavor, especially at the end of season. Best for pick-your-own and direct-to-consumer sales. A standard cultivar in the Southeast for many years. Smaller berry size at the end of the season, but better flavor. Berry deformation in the early season is common. Fairly rain tolerant.

Recommended for: AL, AR, GA, NC, SC, and VA. Standard in NC. Adapted to AR but not widely planted.

Mid-to-late season. Medium dark red fruit, with good size fruit and high yield (Figure 2-2a and Figure 2-2b). Fair flavor, firm berry. Good for wholesale or pick-your-own. Disease and rain tolerant.

Recommended for: AL, AR, NC, VA

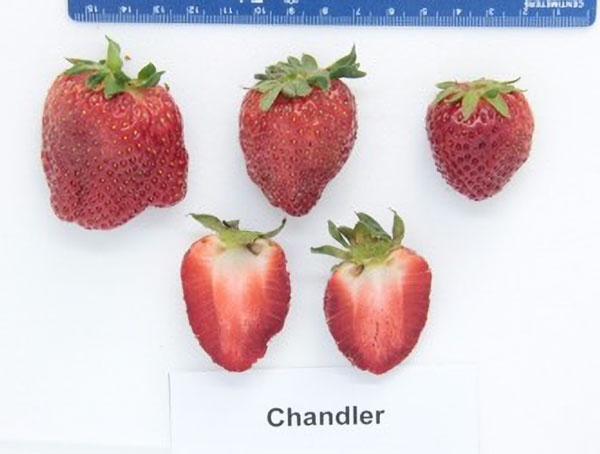

Mid-season. Medium-to-small-size fruit, moderate-to-high yield that has steady production through the season (Figure 2-3). Good flavor. Fruit can be very soft. Fruit size can be inconsistent. Not rain tolerant. Best for pick-your-own and other direct-to-consumer sales. Chandler is adaptable to many regions. Widely planted in the Southeast.

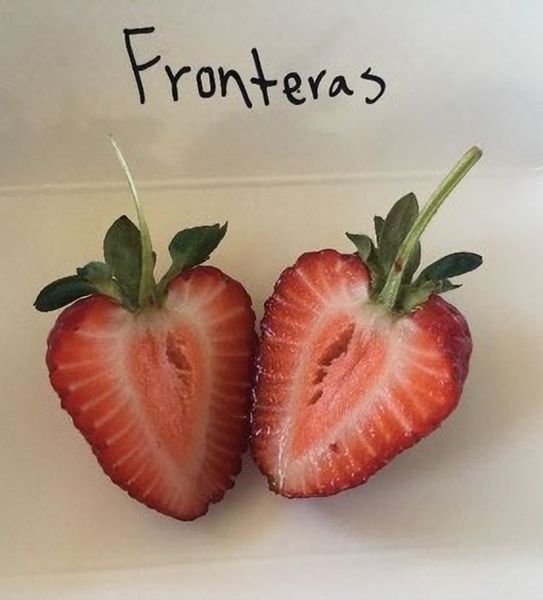

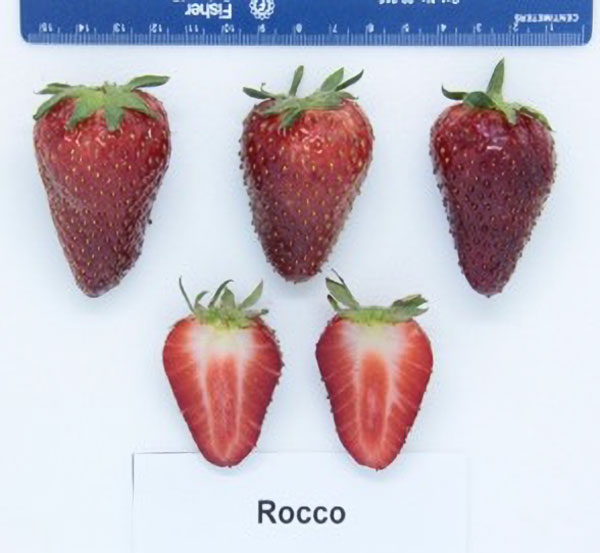

Mid-season. Large uniform berry and high yield (Figure 2-4a and Figure 2-4b). Very firm fruit with fair flavor. Best for mostly wholesale markets. Flavor noted to be good in Arkansas but variable in North Carolina. Color has also been noted to be variable in NC. Not rain tolerant. Spring fertigation most likely different to Chandler or Camarosa.

Recommended for: Areas in NC, SC, and GA. Has performed well in trials in AR.

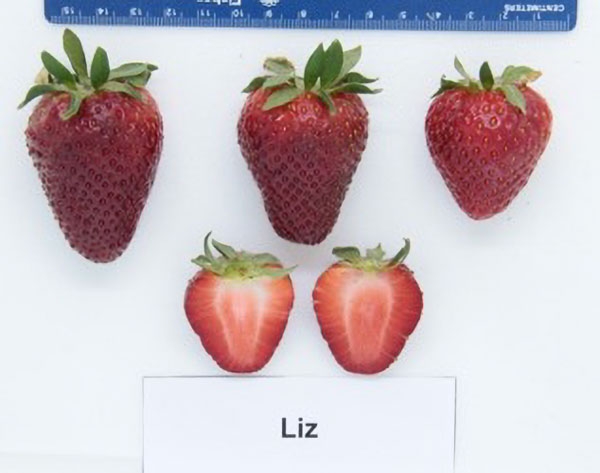

Mid-to-late season. Medium-size fruit and high yields (Figure 2-5). Moderately firm, with improving flavor in late season. Best for pick-your-own and other direct-to-consumer sales. Can develop large canopy in some locations. Fairly tolerant to rain.

Recommended for: NC. Has performed well in trials in AR.

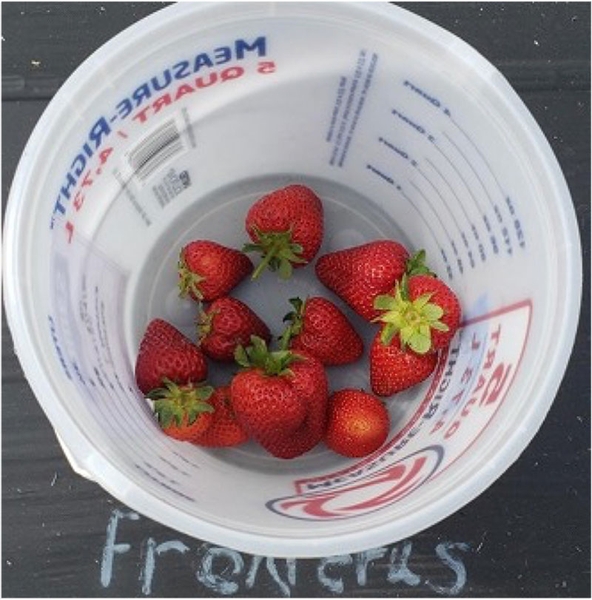

Early season. Small-to-medium-size fruit, steady yield through season (Figure 2-6). Soft. Very unique and good flavor. Seeds sometimes at or on the surface of fruit. Best for pick-your-own and other direct-to-consumer sales. Consider as a Sweet Charlie alternative. It will start at same time or before Sweet Charlie and will continue to fruit through the season. Berry size will be reduced with a heavy crop. Not tolerant to rain.

Recommended for: NC. Has performed well in trials in AR.

Early-to-mid-season. Outstanding flavor, moderately firm, steady and high yield through the season (Figure 2-7). Uniform fruit size over the season. Good for pick-your-own, direct-to-consumer and wholesale markets. Has become a standard in NC. Consider as a Chandler alternative. Planting date comparable to Camarosa, important to achieve good yields. Needs higher N input. Fair-to-good tolerance to rain.

Recommended for: AR, NC, SC, GA, and VA.

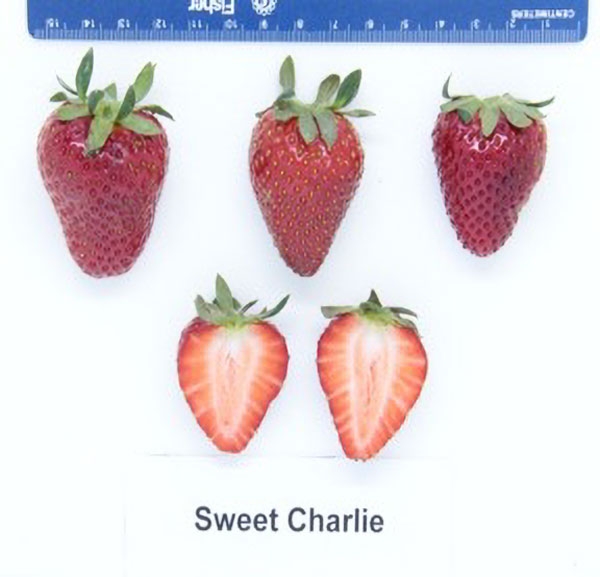

Early season. Medium-size fruit, low yield (Figure 2-8). Good flavor, sweet and aromatic, with soft fruit. Early pick-your-own and other direct to consumer sales. Some growers plant a small acreage of Sweet Charlie to have early fruit to start the season. Very early frost protection necessary. Cultivar may ripen seven to 14 days before Chandler. Not tolerant to rain. Very difficult to manage in many areas.

Recommended with caution for: AR, NC, and VA.

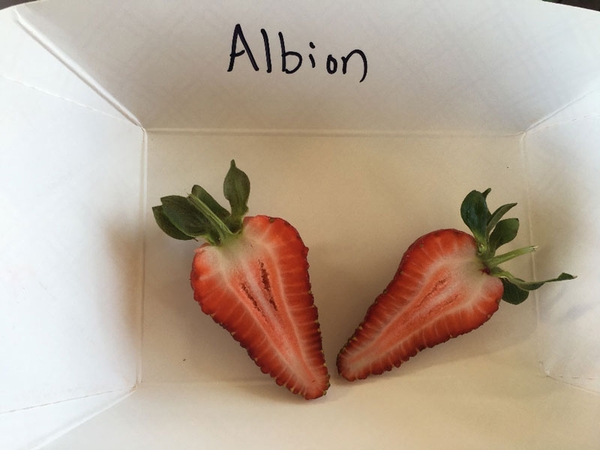

Mid-season. Medium-to-large size, moderate yield in spring (Figure 2-9a and Figure 2-9b). Good to very good flavor. Good for low tunnel, high tunnel, and greenhouse operations. Good for direct-to-consumer sales and wholesale markets. Plants need more nitrogen than standard recommendations. Attracts two-spotted spider mites. Not tolerant to rain.

Recommended for: By far the most commonly grown LD-type cultivar in the Southeast. Recommended for tunnel and greenhouse for AR, NC, SC, and NC.

Medium-large berry, and higher yield than Albion. Fair flavor and firm. Good for low tunnel and high tunnel production. Good for direct-to-consumer sales and wholesale. Plants need more nitrogen during spring than is the standard recommendation. Not tolerant to rain.

Recommended for: NC, especially for tunnel production

Many cultivars have been trialed at locations across the Southeast. Below is a list of cultivars from UC Davis, the University of Florida, and Lassen Canyon that have performed reasonably well in research trials. Miss Joe and Ashley Jay are new cultivars, released in 2021, that seem to be promising but will have to be trialed further. However, annually updated trial data can be found on the NC State Extension Strawberry Growers Information page and the University of Arkansas’ UAEX Arkansas Fruit, Vegetable, and Nut Update blog.

University of California-Davis

Merced, Cabrillo, Portola, San Andreas

University of Florida

Florida Sensation

Good Farms

Miss Joe, Ashley Jay

Strawberry growers in the Southeast have to develop and find niche markets in which they can sell produce for higher price points. Virtually all strawberry farmers have a direct-to-consumer component to their operation, most of whom rely 100% on those sales. Larger farms also sell wholesale and for processing. What works for each farm will depend on a number of factors including location, time, availability of labor, marketing skills, and storage and transportation capabilities. A thorough market analysis is an important first step in deciding the best markets an operation should target.

Wholesale markets may include other farm stands or farmer’s markets where the grower can off-load berries in bulk. Other options in this category include sales to grocery or other local specialty stores, restaurants, or produce distributors for large-scale farms.

Examples of value-added items are ice cream or frozen yogurt, smoothies, baked goods, wines, ciders, jams, and jellies. Berries destined for processing could be marketed using off-farm options, where a grower sells in bulk to a processor, or on-farm options, where the grower is set up to process certain value-added products on-site.

PYO (or “u-pick”) operations are by far the most common strawberry marketing model in the Southeast (Figure 2-10). In many areas, the customer base has slowly shifted towards the purchase of smaller quantities of berries, picked mostly for direct consumption. Many operations are using online pre-booking services for PYO as well as pre-ordering and pre-pick services. PYO operations are becoming a recreational activity for customers, especially if located close to population centers. This model has been extremely successful, allowing operations to be more efficient while additionally offering value-added products or recreational activities. We have assembled a list of important considerations for the successful establishment of a strawberry PYO operation.

This section provides an overview of a sample cost-and-return budget for a strawberry growing PYO operation in North Carolina. This budget serves two main purposes: to provide a new grower an overview of the processes necessary to grow strawberries in North Carolina, and a broad projection of potential net returns; and to provide a template budget for a new or established grower to adapt for their operation and calculate their own net returns.

The detailed enterprise budget breakdown can be found in the Appendix of this production guide. The budgeting program used in this chapter was modified from a program originally developed in 2015 by Olya Sydorovych, Barclay Poling, and Frank Louws at North Carolina State University (Sydorovych et al. 2015).

The budget was developed for a five-acre PYO and pre-pick operation, although costs and returns are discussed on a per-acre basis. The activities and quantities in the production system were developed in conjunction with NC State Extension specialists and agents to align with current recommended growing practices. Prices were obtained from suppliers operating in North Carolina and from online sources. A draft of the budget was checked by a convenience sampling of Extension agents and North Carolina growers for accuracy and relevance. The specific products listed in the budget are used as examples, and their inclusion should not be considered an endorsement of these products over others.

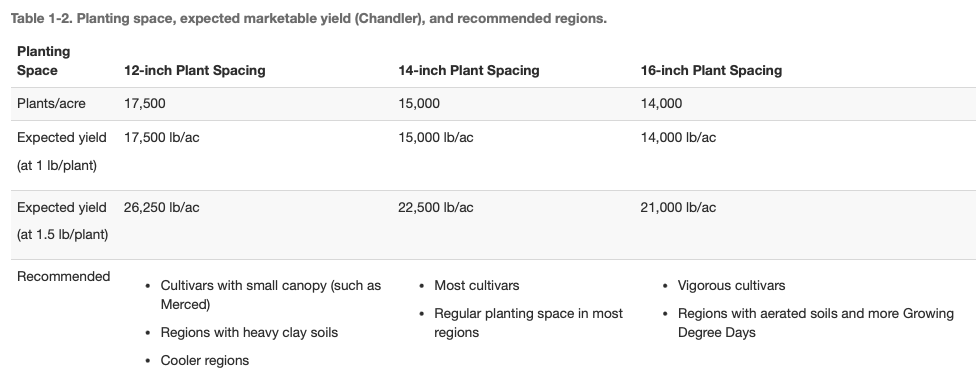

The costs and returns are highly dependent on the assumptions fed into the budget. It is assumed that the grower plants 15,000 plug plants per acre on plastic-covered rows. If good management practices are followed, and the weather is favorable, this system is assumed to return 1.1 pounds of marketable strawberries per plant, or 16,500 pounds per acre. It is assumed that 40% of the crop is sold as PYO, and the remaining 60% sold on-farm as pre-pick. Pre-pick prices are generally higher than PYO prices, due to the additional labor necessary for pre-pick harvest. It is assumed that both PYO and pre-pick strawberries are sold in 4-quart baskets. PYO baskets are sold at $12 per basket ($2.18 per pound), and pre-pick baskets are sold at $18 per basket ($3.27 per pound). It is assumed that pre-pick strawberries will be sold in the 4-quart buckets in which they were picked. If they were sold in small containers, such as single-quart pulp cups, the cost of the pulp cups would need to be added. Selling the 9,900 pounds of pre-pick in pulp cups would add approximately $1,500 in costs, at a cost of $0.15 per pulp cup. The labor expense was assumed to be $15 per hour, which includes the base wage rate plus taxes, benefits, and other overhead. This labor is assumed to be hired from the local community. The owner’s time is assumed to be valued at the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ average rate for agricultural managers, $32.73 per hour. Harvest laborers are assumed to be paid on a piecework basis at a rate of $1.50 per 4-quart basket. Assuming a harvester can pick 50 pounds per hour and 5.5 pounds per bucket, this equates to $13.65 per hour. The returns in this budget will be under- or overstated if the grower has faster or slower pickers. Some growers use H-2A labor for cultural management and harvest. This can be represented in the budget spreadsheet by updating the employee expense cost, which should reflect the prevailing H-2A labor rate along with H-2A overhead costs, including housing and transportation to and from the picker’s home country (if appropriate). The harvest window was assumed to occur over a six-week period in the second two weeks of April and throughout May. The quantity available for harvest varies from week to week, with an associated change in harvest labor and other input costs. Here it is assumed that harvest quantity increases until the third week before tapering off.

Machinery and equipment costs are calculated as if the entire cost is attributed to the strawberry operation. For many pieces of equipment, such as tractors, this will overstate the cost to the strawberry operation. These costs are calculated on a per-hour basis, assuming a certain purchase price, salvage value, and lifespan of each piece of equipment. Machinery costs also include the variable costs of operating the equipment, including fuel, lubricant, and repairs. The costs of fumigation, bed-shaping, and laying mulch are included as a custom operation at a rate of $2,250 per acre. However, the costs of a fumigation rig are included in the machinery calculation spreadsheet for the grower who wants to calculate the cost of doing their own fumigation.

The cost of purchasing an overhead irrigation system and a drip irrigation system can be quite substantial. The cost will vary on the system chosen and the geography of the field, but the cost for installing a system may range between $15,000 and $30,000. This one-time set-up cost is not included in the strawberry budget, although the per-hour cost of using the systems, including depreciation of the purchase price, is included. Land rental rates vary substantially across North Carolina. This budget assumes a $150-per-acre net land rental rate, but the reader is encouraged to use their own land rental rate. The budget also assumes that growers rent one beehive per acre for pollination services at a rate of $50 per hive, and a toilet and hand-washing facility for the two months during harvest season at a rate of $150 per month.

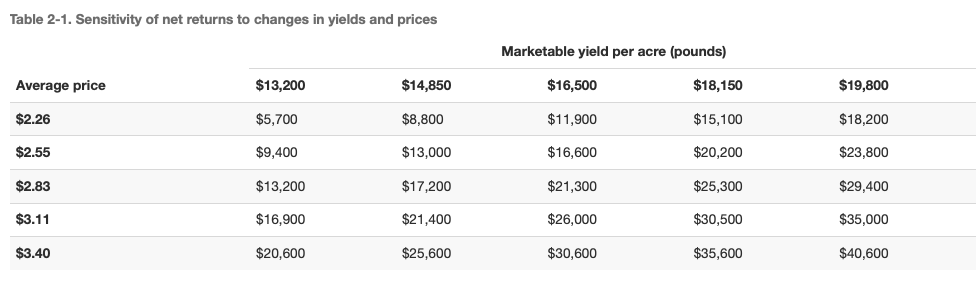

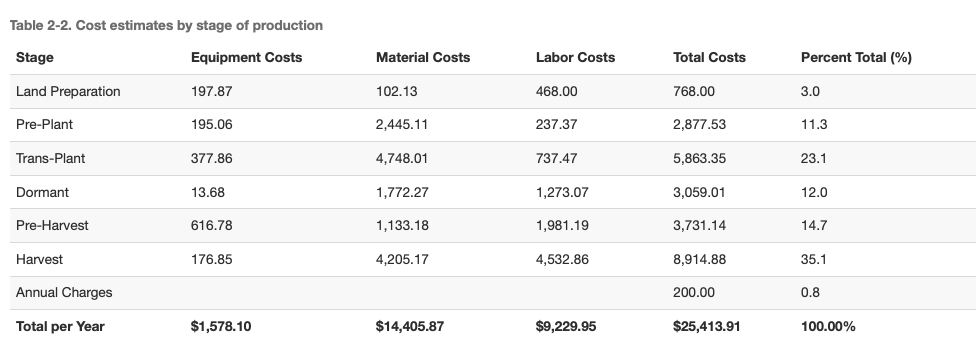

With the assumptions discussed above, the expected gross revenue for an acre of strawberries is $46,800. The expected production costs are $25,413.91 per acre, for a net return of $21,386.09 per acre. These numbers, however, give a misleading sense of certainty to the profitability of a North Carolina strawberry operation. Any changes in market price, yield, production system, or input prices will change the expected return of the enterprise (Table 2-1). Holding yields constant, a 20% reduction in price would decrease net returns to around $13,200, and a 20% increase in price would increase net returns to around $29,400. Holding price constant, a 20% decrease in yields pounds per acre would decrease net returns to $13,200, and a 20% increase in yields would increase net returns to $29,400. If both price and yield fell by 20%, net returns would fall to $5,700 per acre, and if both price and yield increase by 20%, net returns would increase to $40,600 per acre.

Table 2-2 shows the expected costs by stage of production. Costs are broken down into equipment, material, and labor costs. The percentages of total costs from each stage of production are also presented. The most costly stage of production is harvest (35.1%), when large material and labor costs are incurred. The largest equipment costs are incurred during the pre-harvest stage, and the largest material costs are during the transplant stage when plug plants are purchased.

The sample budget published in the Appendix provides an estimate of the potential returns to a PYO and pre-pick strawberry operation in North Carolina and can be a starting point for an existing or potential grower to estimate their own costs and returns. Growing strawberries, like any high-value specialty crop, is a risky business, requiring suitable management skills, access to labor, appropriate machinery and equipment, a stable marketing channel, and favorable weather conditions. It is recommended that a grower considering embarking on strawberry production prepare a cost-and-return study for their specific circumstances, and consult in advance with knowledgeable experts, including Extension agents, sales representatives, and experienced growers. A good overview of existing strawberry budgets in other regions can be found on NC State’s Agricultural and Resource Economics website.

Soils. Strawberry plants thrive best in sandy loam or sandy clay-loam soils. Soils higher in sand content allow for easier water penetration and aeration. A grower may need to supply fertilizer more often on a sandy soil during the harvest season compared to soils with high clay and organic matter content. However, soils with high clod, clay, or stone percentage will not form well-shaped beds and can become waterlogged easily.

Water drainage in field. Standing water in a field, even in row middles, can reduce yield and access. A well-drained field will be more productive and can handle the common heavy rainfalls in the Southeast better.

Air drainage. A strawberry field should be planted in an area that provides sufficient air drainage. Ditches with standing air can become a challenge when frost- or freeze-protecting in early spring. On the other hand, too much wind exposure can damage young plants and can blow off floating row-covers. Sites in proximity to tree lines, but not in the shade, can be optimal strawberry production sites.

Soil pH. Strawberries need a soil pH from 6.0 to 6.5 to reach optimal production. A main activity for growers in the Southeast is adjusting pH before bed-laying. We recommend taking soil samples to evaluate lime and fertilizer needs three to four months before bed-laying. Soil samples need to be taken from a depth of 6to 8 inches in a zig-zag scheme across the field (Figure 3-1).

If the soil pH is acidic, dolomitic limestone needs to be added to increase the pH of the soil.

Row orientation. For optimal strawberry growth, rows should be orientated in a north-south direction to ensure uniform plant development and ripening.

Windbreaks. Having windbreaks on the north and northwest sides of the field is advantageous as it helps reduce losses from windborne freeze events that occur in late winter and early spring (Poling 1993). Too much protection from wind can increase disease pressure, while frequent exposure to high winds could harm new growth (Poling 1993).

Pre-plant fertilizer. The amount of pre-plant fertilizer should be determined by a soil test two to three months before bed-shaping. Fertilizers are often evenly broadcasted before bed formation. Phosphate, sulfate, and potash concentrations should be determined based on the soil report. We recommend applying a maximum of 60 pounds per acre of nitrogen for Chandler and Camarosa as pre-plant. Research suggests that for those cultivars, even lower amounts of nitrogen as pre-plant fertilizer might be sufficient, depending on the soil type (Lay et al. 2023; Miner et al. 1997). However, other cultivars might require more pre-plant nitrogen. Guidelines for pre-plant fertilization can be found in the Appendix. The North Carolina Department of Agriculture Agronomic Service has additional strawberry fertility recommendations.

Pre-plant fertilizers are commonly sourced from sulfur-coated urea (46-0-0), diammonium (18-46-0) or triple superphosphate (0-46-0), potassium nitrate (13-0-44), potassium sulfate (0-0-50), potassium chloride (0-0-60), or ammonium sulfate (21-0- 0). The recommended fertilizer source for potassium is potassium sulfate. Ammonium nitrate is the usual pre-plant nitrogen fertilizer (Poling 1993). Many growers also apply granular, full-spectrum pre-plant fertilizers such as 6-6-18 or 10-10-10. If organic fertilizer (such as manure) is used in combination with chemical granular fertilizer and an additional sulfur source, it is important to have the organic fertilizer analyzed for nutrient content before application.

Soil preparation and bed formation. Avoid larger stones, clumps, sticks, and undecomposed plant material. In heavy clay soil, disking will help to break down the large clods before bed shaping. Soil beds are made with a tractor-towed bed shaper, are usually 6 to 10 inches high, and have a 30-to-36-inch top width and a 5-to-6-foot row width (Figure 3-2). In many cases, pre-bedding is recommended before plastic mulch is laid. A tight fit of the film is important on the beds along with good tucking on the edges to prevent wind from blowing the plastic up and damaging the plants.

Furrow area. After the beds are made, it is desirable to seed the furrows with annual ryegrass at 50 pounds per acre. Once established, ryegrass will help reduce the washing of the topsoil after periods of heavy rainfall or after growers have employed overhead sprinkler irrigation. This will aid with crop plant establishment and for frost protection in early spring, particularly in fields with a slope greater than 2% (Poling 1993).

This chapter describes fumigation and briefly discusses factors that should be considered when deciding whether to include fumigation as part of a pest management program in strawberry plasticulture production. Additional details for fumigation in strawberry plasticulture production are available on the Southern Region Small Fruit Consortium website.

Fumigants currently available for use in strawberry production include the active ingredients chloropicrin; 1,3-dichloropropene (1,3-D); metam potassium; metam sodium; and allyl isothiocyanate. These active ingredients are available under various trade names alone or in various combinations. These fumigants are not approved for use in organic production; therefore, fumigation would not be an option for organic strawberry production for an organic market.

Fumigation is a process that involves injecting a chemical fumigant into the soil. Fumigants are most often liquids under pressure that form a gas once injected, and they have pesticidal activity against various pests, depending on the fumigant. As the fumigant is injected into the soil, the soil and fumigant are immediately covered and sealed with plastic. The gas then spreads through the soil treatment area—the higher the vapor pressure of the chemical, the more uniformly the fumigant will spread.

Fumigation requires the use of specialized equipment (Figure 3-3) and the appropriate training and use of personal protection equipment (PPE; Figure 3-4) for applicators and handlers. Typical fumigation equipment used in the Southeast includes a single-row bed-shaper and plastic layer with a fumigation shank. Fumigation must also be performed prior to planting with 14 to 21 days (depending on label directions) between application and planting. Fumigation provides improved management for weeds, soilborne insects, and pathogens, particularly nematodes and black root rot, which can reduce strawberry yields.

There are various types of fumigant equipment that may be required, depending on the fumigants utilized. The most common fumigant equipment uses a nitrogen tank to push the fumigant through a line to a shank where the fumigant is injected. These rigs generally include a single-row bed-shaper, drip tape roll, and plastic layer directly behind the fumigation shank to form a sealed bed that is ready for irrigation once needed (Figure 3-3). This equipment has been commonly utilized for application of 1,3-D products, as well as combinations of 1,3-D and chloropicrin. Some 1,3-D and chloropicrin combination products have also been registered for injection through drip tape as well. Unless a specialized rig is utilized, the injection of metam sodium and similar products requires two additional passes for injection and rotovating prior to laying the drip tape and plastic.

A table outlining the efficacy of each fumigant against these pests is available in the University of Georgia Extension’s Southeast Regional Strawberry Integrated Pest Management Guide Focused on Plasticulture Production. Additional details on equipment calibration and fumigant calculations are available on the Southern Region Small Fruit Consortium website.

Soil structure, temperature, and moisture influence the effectiveness of soil fumigation. Soil should be free of plant residue and clods. Soil should be cultivated two to three weeks before fumigant application. Fields should be subsoiled in two directions to break up hardpans. After hardpans are broken, chisel plowing will break up large clods. During fumigation, soil temperatures should be between 45°F and 80°F, and soil moisture should be between 60% and 70% of field capacity. During periods of dry weather, irrigating a day or two before a planned fumigation can optimize conditions for fumigation.

When fumigating, personal safety is a priority. The most common routes of fumigant exposure are through inhalation or direct contact with eyes or skin. Fumigants can also dissipate into the air very quickly, and exposure can occur without warning. Therefore, PPE is required any time fumigants are applied or handled, including when hooking up gas cylinders, calibrating the fumigation rig, applying the fumigant, cleaning the fumigation rig, and storing the fumigants. The appropriate minimum PPE that must be worn for each fumigant is described on the fumigant label. Minimum PPE often includes a full-face, fit-tested, air-purifying respirator with the appropriate cartridge; appropriate chemical-resistant rubber gloves and boots; clothing with long sleeves and pants; and a full-body Tyvek suit (Figure 3-4).

Various types of plastic mulch, including polyethylene plastic (PE), metallized film, virtually impermeable film (VIF), and totally impermeable film (TIF), may be suitable for use in fumigation. These mulches vary in cost, ease of application, and fumigant permeability, and may have other advantages or disadvantages in terms of pest management and durability. No biodegradable plastic mulch is allowed with soil fumigation. Additional details on the advantages and disadvantages of each of these types of mulch are available on the Southern Region Small Fruit Consortium website. Consult fumigant labels to determine the appropriate type of mulch and the required plant-back period for that specific fumigant.

As with any pesticide application, successful application requires the use of well-maintained, appropriate equipment as well as appropriate equipment calibration and fumigant calculation to ensure application of the appropriate fumigant rate. All equipment should be regularly maintained and inspected prior to use for cracked hoses, rusty fittings, or other broken parts prior to hooking up a fumigant or gas cylinder. Custom fumigant applicators must have access to all training, equipment, and fully understand all EPA regulations required for fumigant application.

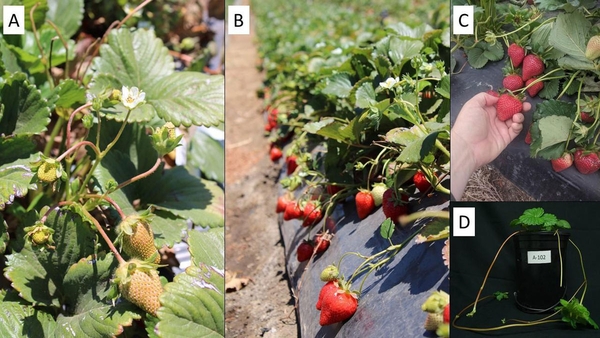

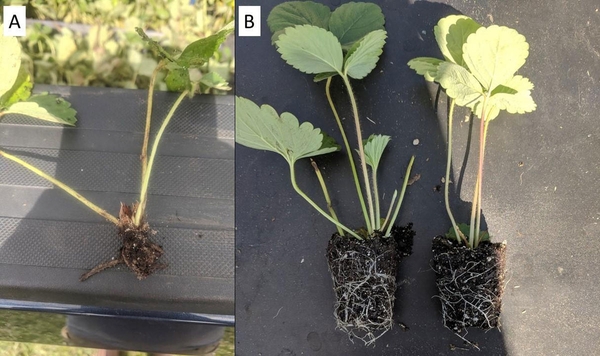

Commonly used plant materials in the Southeast are bare-root plants, plug plants, and “cut-off” plants (Figure 3-5). Other plant materials that may be available but are rarely used include Frigo plants and tray plants.

Bare-root plants, cut-off plants, and fresh dugs. These are plants that were grown in an open field nursery (usually in Canada or California), removed from the field, and shipped to the grower within a few days. Those plants can be stored in refrigerated environments for about a week after the initial dug date before losing quality. A high-quality bare-root plant consists of a single crown of about one half to one inch in diameter with a fibrous and dense root system. Cut-off plants have no leaves attached. Those plants are typically cheaper than plug plants and are easier to ship but more difficult to establish. Overhead irrigation for seven to 10 days after planting will have to be applied to initiate plant establishment. It is recommended that those plants are planted one week before the recommended plug plant planting date. A large problem with planting bare-root plants of any type is “J-rooting.” This happens when plants are inserted into planting holes that are too small. Cut-off plants are especially more sensitive to planting conditions, including planting depth and temperature. It is not recommended for beginners to use a large acreage of cut-off plants. Freshly dug bare-roots and cut-offs are usually delivered in crates of approximately 1,000 plants, which should be kept cold (between 35°F and 40°F) prior to planting. Plants should only be held for a few days before planting.

Plug plants consist of strawberry daughter plants (runner tips) which have been rooted into 50- or 38-cell trays. Plug plants are widely available in the Southeast, easier to plant, and can typically be planted later than bare-root plants. Plug plants are usually rooted by local companies that purchased runner tips from nurseries in Canada and elsewhere. Plug plants are more expensive than bare-root plants. Plant availability starts in early September and continues through the end of October for much of the Southeast. Plug plants are by far the most common method to plant strawberries in the Southeast. Plug plants are easily planted by hand. Mechanical-assisted planting, such as with a water wheel transplanter, is possible. However, it is important to ensure the crown of the plug plant not be buried or sticking out above the soil line for optimum plant establishment. Plug plants should be planted into a moist bed, and once planted should receive frequent and short irrigation to maintain the soil moisture around the plug. In hot weather, overhead irrigation is advised during the first two weeks of establishment.

Other plant types. Frigo plants are similar to cut-offs but stored at below-freezing temperatures for later planting dates. Frigo plants are often used in other parts of the world for early summer plantings. Tray plants (or “60-to-70-day plants”) are typically rooted for 60 to 70 days in 250-cc or 125-cc trays and have more established crowns compared to plug plants. Tray plants are the standard plant for strawberry greenhouse production along the east coast. For a selection of strawberry nurseries, please consult the Appendix.

Plant spacing. Plants are generally staggered or offset in a double row with a space of 12 to 16 inches between plants and between the rows. Holes for planting both plugs and bare-root plants can be punched by hand, using homemade tools or a water wheel transplanter. Planting holes for plug plants should be conical and about 2 inches deep. Planting holes for bare-root and cut-off plants need to be deeper, usually around 4 to 6 inches, to avoid J-rooting of plating material.

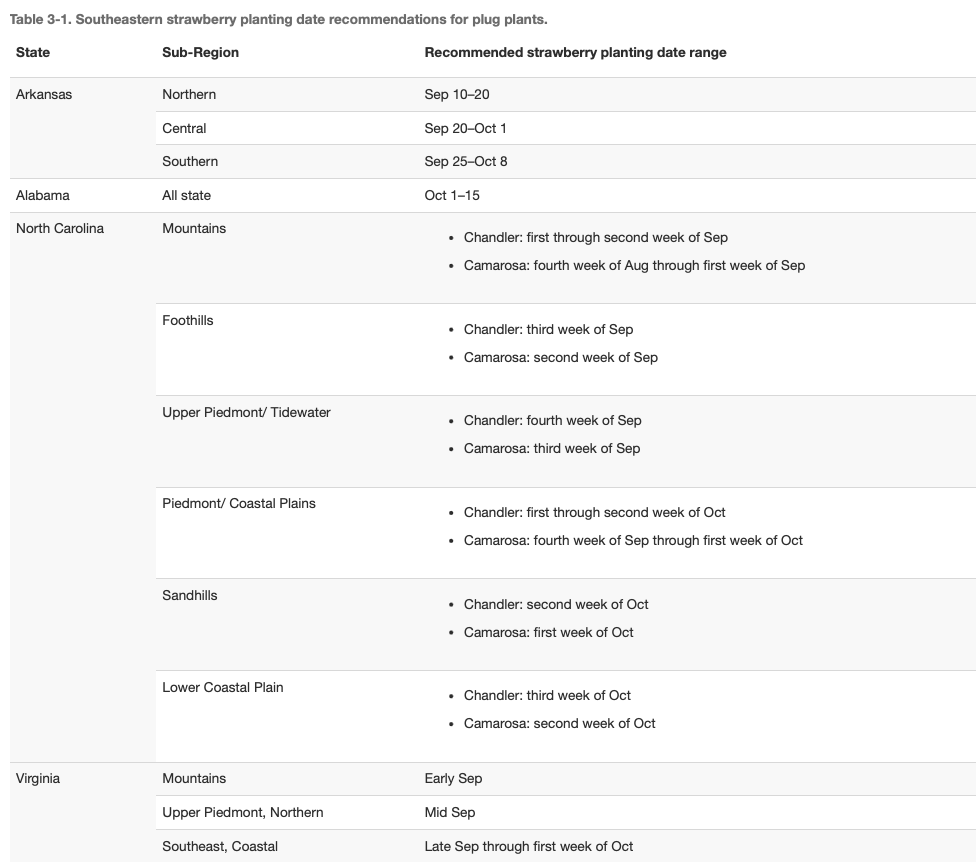

Planting date. Timing of strawberry planting in the fall has a large impact on the potential yield of the strawberry crop the following spring. Generally, any bare-root or cut-off material needs to be planted about three to five days earlier than plug plants (Figure 3-6; Table 3-1).

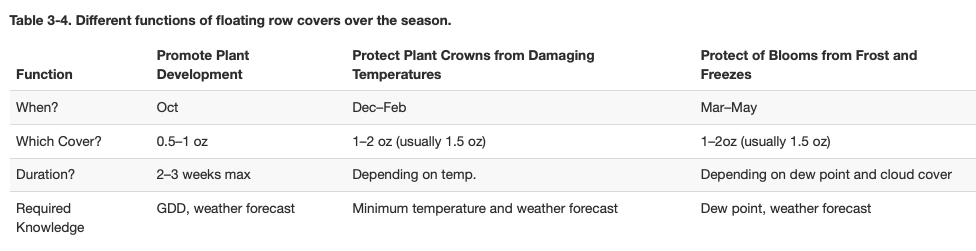

Fall Row-cover Use on Late-Planted Crops. Generally, floating row covers (between 0.5 and 1.5 ounces) can be used in the fall to increase the amount of heat units given to a strawberry plant. This is especially important when cultivars such as Camarosa, Fronteras or Ruby June are planted too late (Table 3-1). These cultivars require a certain amount of heat units (Growing Degree Days, or GDD) before winter to improve floral development in branch crowns (Figure 3-6). The application of floating row covers helps to offset the detrimental effect that a late planting date can have on yield in certain cultivars.

Typically, floating row covers to increase heat units should be used before the end of November, if daily high temperatures are predicted to be lower than 70°F. Prolonged row-cover use can result in disease spread and reduced pollination. Botrytis gray mold and spider mites in particular can become a concern under row covers. Disease and pest management before row-cover application and after removal is recommended. Please consult the Southeast Regional Strawberry Integrated Pest Management Guide Focused on Plasticulture Production for more guidance.

Row-middle management. Planting a grass in the row middles limits soil erosion, suppresses weed growth, and improves accessibility of row middles. Typically, annual ryegrass is broadcast-seeded just after laying beds, shortly after transplanting. Seeding rate for annual ryegrass is 25 pounds per acre (only in row-middles). Ryegrass should establish well with rainfall but will need to be mowed to maintain a short height. Tall ryegrass can interfere with row-cover applications and can eventually shade the plants and limit air movement. An alternative to annual ryegrass is black seeded oats (cosaque oat), which are generally slightly cheaper than annual ryegrass. Black seeded oats have been used in Arkansas for row-middle plantings. The plants retain a short habit throughout much of the fall and winter seasons similar to annual ryegrass, but will also require mowing to reduce plant height during picking in the spring.

Plug plant irrigation and establishment. After planting plug plants, overhead irrigation and drip irrigation are needed for plant establishment. In North Carolina, apply overhead irrigation at a rate of 0.10 inches per hour for 5 hours the first day, 3 hours on the second day, and up to 2 hours on the third day, depending on weather conditions. Drip irrigation should be continued on a regular basis, depending on weather conditions. If conditions are dry, daily drip irrigation for 1 to 2 hours is warranted.

Bare-root irrigation at establishment. Overhead irrigation should begin immediately (delayed by no more than one hour) after the plants are set. Irrigation for 7 to 14 days after transplanting may be required depending on weather conditions. Overhead irrigation should cover the entire field evenly, including field edges with a small amount of water, typically 0.10 inches per hour. At the end of the establishment period, each plant should have two or three vigorously growing, fully green leaves.

General irrigation advice for fall. Continue irrigation based on weather and plant development throughout the fall is critical. Young transplants can quickly wilt when temperatures are above 80°F or if conditions are dry. Active root growth occurs throughout the fall as long as temperatures remain above 45°F.

Runner removal. Runners should be removed by pinching or trimming before dormancy, usually in November or early December. While labor intensive, runner removal refocuses the plants’ energy toward root and crown development. In some regions, runners will have to removed twice between transplanting and dormancy, usually four weeks after transplanting and then again in November and December.

Strawberry plant propagation. Most strawberry cultivars are patented and licenses are required for propagation. Furthermore, open-field strawberry nurseries are very complicated multi-field and multi-year operations by themselves. They rely heavily on methyl bromide fumigation, a rigid spray schedule, and specific climate conditions. Both indoor and open-field strawberry nurseries require a high level of knowledge, high upfront costs, and a substantial investment in annual operational costs. It is highly recommended to consult with Cooperative Extension as well as with other growers before investing in a strawberry nursery.

NC State Extension provides timely regional frost and freeze advisories for strawberry growers every season. These forecasts cover a region from Maryland to South Georgia and are available on the NC State Extension Strawberry Growers Information page. Once subscribed via email, timely frost and freeze advisories will be distributed at a minimum of 24 hours before the event.

Freeze and frost events frequently threaten strawberry production in the Southeast, resulting result in yearly losses across the region. The level of vulnerability of a strawberry plant to cold temperatures depends on its physiological stage and its acclimatization (Table 3-2). A fully dormant strawberry plant is generally less vulnerable to cold temperatures than a plant that is active.

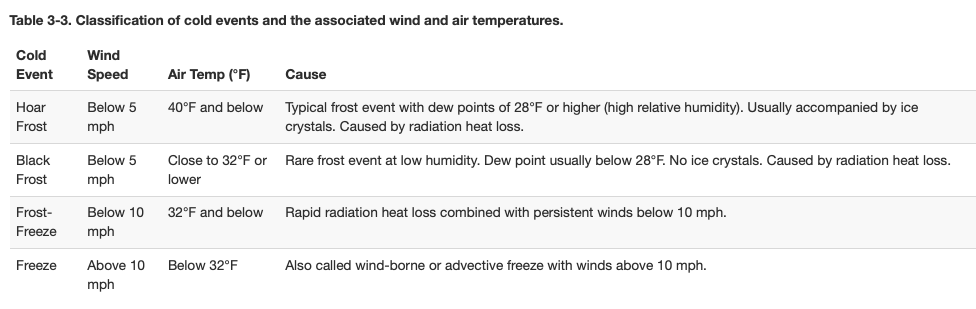

Most vulnerable to cold injury are open blossoms (Figure 3-7). Blossoms can be damaged at temperatures around 30°F. This risk is increased during radiation weather events (such as an early spring frost), in which wet bulb temperatures fall below 30°F, even if ambient air temperatures are higher. Such weather events are very common in the South, dangerous to strawberries (as to a variety of other crops), and require preparation and constant monitoring. A range of tools are available to strawberry growers to mitigate the potential damage than can occur from cold weather. In this section, we explain what characterizes different cold events, how to read and understand weather forecasts (especially during spring frost events) and how to protect strawberries from freeze and frost events.

Generally, cold events can be classified into three different categories (Table 3-3): frost events, frost-freeze events, and freeze events. It is crucial to understand the differences between cold events that can occur over the season. Most frosts are radiation events, usually occurring in the spring during an inversion weather situation. Frost generally occurs when the temperature of a surface is equal to or lower than the dew point of 32°F. This is often the case on cloudless, cool nights that generate heat loss due to radiation. Radiation occurs when warmer temperatures during daylight hours heat plants and the soil. Cloud-free skies and cooler temperatures at night cause heat to re-radiate away from those surfaces. Clear nights with air temperatures of 40°F or lower, and dew points of 32°F or lower, are at high risk for frost. While the National Weather Service might issue a frost warning at temperatures above 32°F, it does not mean that a radiation frost will necessarily occur at a specific field. It is therefore important for strawberry growers in the Southeast to understand the dynamics and weather patterns at their particular location.

Radiation frost nights are a common threat to strawberry growers in spring, when strawberry blossoms are out and the plants are most vulnerable. Hoar frost events are by far the most common cold events during spring in the South, characterized by clear nights and wind speeds less than 5 mph. Hoar frosts are accountable for over 90% of all frost events, often indicated by water crystals forming on surfaces in the field (such as pipes and grass). A less-common frost type is black frost, occurring on radiation days characterized by minimum air temperatures close to freezing combined with low humidity. These frosts are less visible and therefore more dangerous. Typically visible ice crystals are absent in a black frost, and thus paying attention to weather forecasts, especially dew point predictions, cloud cover, and predicted minimum temperatures for a specific location, is even more critical.

Frost-freeze events are typically longer in duration (more than 10 hours), caused by a mix of radiation and persistent winds. Unfortunately, frost-freeze events become more common in early spring. Compared to radiation frost, protecting open blossoms from frost-freeze events in spring are among the most difficult tasks a strawberry grower faces in the South, due to generally lower temperatures and higher wind speeds.

Windborne (advective) freeze events are caused by moving air masses, bringing cold air from northern weather systems into the Southeast. While this happens frequently in winter, spring freeze events are rare. However, spring freezes can be very dangerous, last for several days, and bring significantly colder temperatures at a time when strawberries are most vulnerable. One of the most memorable spring freeze events was in April of 2007, when five days of freezing weather had a significant impact on farming all across the East Coast, including Florida (Poling 2008). Windborne freezes are common in winter. During dormancy, protection with floating row covers is recommended when predicted air temperatures drop below 15°F.

Different cold weather events will require different responses and approaches to protect strawberry plants from cold injury (Figure 3-9). To select an appropriate management plan for a predicted cold weather event, it is important to have a reliable weather forecast and to formulate an idea about what the forecast means for your region and your specific site. In spring, air temperature predictions alone are insufficient to make good decisions about strawberry cold protection strategies. Temperatures at the plant level can differ vastly from the predicted air temperatures, and wind speeds and dew-point readings are important to consider when determining which weather event to expect (Figure 3-9).

A floating row cover under low wind speeds can be used to protect from frost, frost-freeze, and windborne freeze events (Table 3-4, Figure 3-10a). However, there are several limitations to row cover use. Floating row covers in the field are often very labor intensive to deploy (it takes two or three people for a 200-by-60-foot row cover). Row cover use can promote disease and pest development, and additional disease and pest management (such as for mites or grey mold) is often needed. Most importantly, floating row covers can cause damage if not used correctly. For example, row covers deployed during wind gusts of 15 mph or more can cause physical damage to blossoms and strawberry plant tissue. Wet row covers (due to previous rain) have no insulation value and can even freeze directly to the plants, which risks additional damage to strawberry blossoms and plants. However, floating row covers are the main management tool for frost and freeze protection, and if deployed under the correct conditions, can provide important crop protection. A 1.5-ounce row cover can potentially protect open blooms down to a temperature of 24°F at the canopy level.

Frost protection with overhead sprinklers requires maintaining a continuous water-ice interface and an undisturbed tissue-ice connection (Figure 3-10b, Figure 3-10c). Under those conditions, continuous freezing layer releases 80 calories of heat per 0.03 ounce of water. To achieve this, water needs to be supplied constantly starting at dusk until temperatures are high enough for the ice to thaw (Figure 3-10d). This will build up a layer of ice over the tissue. Constant application of water will keep the ice temperature around 31°F or 32°F, slightly above critical damage levels. Consistent droplet size and water coverage is important to provide protection from frost injury. The water-ice layer should be clear at all times, and water droplets should be running off (“running nose”) at all times. Ice layers that become cloudy or that do not show consistent water run-off will damage plant and blossom tissue.

Overhead sprinkler systems require large water sources, high-capacity pumps, a reliable operation in cold temperatures, fast sprinkler head rotation times, and high uniformity in droplet size and distribution patterns. The choice of sprinkler equipment to be used for overhead irrigation is therefore highly important for frost protection. Sprinklers with a minimum rotation time of 30 seconds are recommended. Conventional or hybrid impact sprinklers with a mechanical braking system are needed to handle differences in water pressure. If sprinkler systems use silicone, they might slow down in colder temperatures. Water needs to be distributed uniformly, and droplet size should be consistent over the area that is covered. Differences in droplet size can lead to areas in which plants are not covered sufficiently, leading to subsequent cold injury. Hybrid impact sprinklers with an integrated nozzle and deflector design are recommended to achieve higher uniformity. Systems with nozzles that are easy to assemble and replace are highly recommended.

The frost protection success of a sprinkler system relies on the frequent and uniform distribution of water throughout the night. To successfully protect from frost and frost-freezes using overhead irrigation, water application must start before plant surface temperatures reach a critical dew-point. The lower the predicted dew point, the higher the air temperatures will be when watering should begin. Watering must continue until ambient temperatures at plant level rise above critical dew points.

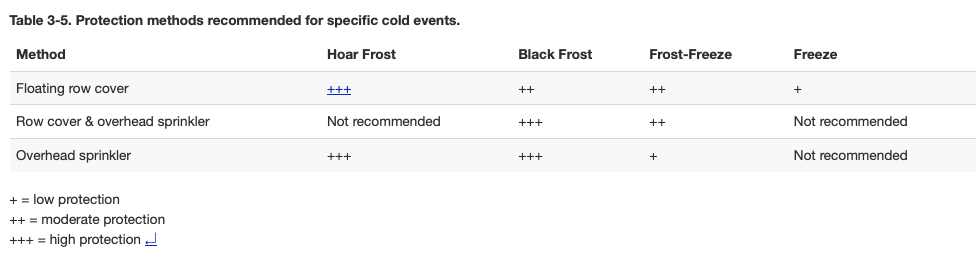

To be prepared for frost and frost-freeze events in the Southeast, we recommend deploying an integrated approach of protection methods in a strawberry field. Table 3-5 gives an overview of recommended cold protection methods, based on the predicted cold event.

In most of the South, late winter and early spring are characterized by very turbulent weather. Cold events in January and February, when night temperatures can reach less than 20°F, can happen quite frequently. However, it is not uncommon that cold weather is followed by warm weather systems and rain, or vice versa. In some years, this can lead to longer warm periods in January and February, and growers will often observe unwanted flushes of early bloom. This is especially true for cultivars that don’t require a lot of heat units to break bud, such as Chandler or Sweet Charlie. If there are blossoms as early as January or February, it typically is not recommended to frost-protect. Once in late February or March, disease and pest management is as important as frost protection. Please consult the Southeast Regional Strawberry Integrated Pest Management Guide Focused on Plasticulture Production. Leaf tissue should be sampled by mid-March at the latest to determine fertility needs.

Harvest practices. To maintain good fruit quality strawberries should be picked at a minimum of twice per week at the beginning of the season, every two to three days during peak season. Frequent harvest ensures that fruit is picked at the peak of ripeness, which improves its holding ability, and that diseased fruit is removed promptly to limit disease spread. Morning harvests are preferred due to cooler fruit temperatures during that part of the day. More frequent harvests during rainy periods are not uncommon to remove ripe fruit from the field prior to a rain event, during which it might be damaged.

Workers and customers should be trained to distinguish ripe fruit from unripe fruit as well as from non-marketable fruit that are too small, deformed, diseased, or have color or softness issues. Sometimes, soft, discolored spots are on the bottom side of the fruit, especially when fruit are touching the plastic. White shoulders on strawberry fruit usually form when provided temperatures are not consistent enough for a uniform color formation. That can be especially the case in early spring. Fruit safety concerns during harvest are discussed extensively in the “Food Safety” section of this guide.

Frequent sanitation of the strawberry field. During normal harvest operations, fruit that is soft, diseased, too small, deformed, soil-covered, or overripe should be removed from the plant and placed in a separate container for removal from the field. It has been a common practice among some growers to leave those fruit (“culls”) in the row middles. However, we strongly advise minimizing this practice as it is associated with disease outbreaks. Weeds or grass in the row middles should be managed to maintain good air-flow and access to the plant. Some growers use herbicides to maintain the row middles without vegetation. If herbicides are used, they have to be applied with protected sprayers to avoid herbicide drift on strawberry plants. For more information, please refer to the Southeast Regional Strawberry Integrated Pest Management Guide Focused on Plasticulture Production. If mowing is used to maintain grass between the rows, a mulching-type mower is preferred due to its ability to drop clippings directly on the ground.

Labor and regulatory compliance. Labor needs are difficult to predict during harvest and vary widely by operation type and the availability of skilled labor. It is important to train labor on fruit ripeness identification and other operational procedures. Small farms often rely on local labor, while large operations often participate in the H2-A program. Two or three trained workers might be able to harvest an acre of strawberries per day during peak season. Food safety compliance is discussed in the “Food Safety” section and in the Appendix. It is also important to use pesticides with adequate pre-harvest intervals. For more information, please refer to the Southeast Regional Strawberry Integrated Pest Management Guide Focused on Plasticulture Production.

Post-harvest handling. Food safety compliance of post-harvest processes is discussed in “Food Safety” and in the Appendix. Generally, shelf life of strawberry fruit will double or triple when stored in a cold environment. Fruit should be stored in a clean and dry environment as soon as possible after harvest, with temperatures maintained close to 32°F.

Irrigation. In annual hill plasticulture systems, irrigation is provided through drip lines under the plastic mulch. In most regions in the Southeast, one drip line (with emitter spacing of 10 to 12 inches) is installed in the bed middle during bed formation. In general, strawberry plants have a shallow and fibrous root system and require varying water amounts depending on plant growth stage, soil type, and weather conditions. Typically, water demands during plant establishment in fall are fewer compared to irrigation demands in the spring. It is important to monitor the stage of the plant and increase watering in spring once you see blossoms on the plants. Depending on crop load and weather conditions, strawberry plants might need as much as 2 inches of water per day. This is often delivered through watering a field three to seven times per week. However, research suggests that irrigation of two to three times during the day ensures that moisture level does not fall below the recommended 50% of field capacity (Klodd et al. 2021). To monitor moisture levels, a tensiometer can be used to indicate when irrigation is needed for a plant (Kirkham 2005).

Generally, sandy and sandy loam soils require more frequent watering compared to clay or clay loam soils due to their reduced water-holding capacity. For additional details on the major components of drip irrigation, pressure regulators, and types of filters to use, refer to NC State Extension Publication AG-489, Plasticulture for Commercial Vegetables.

Spring fertigation. Fertility needs in spring can range from 5 to 10 pounds of N per acre per week (most SD cultivars), and 8 to 12 pounds of N per acre per week, as is the case with most LD cultivars and Ruby June. While nitrogen is by far the most important nutrient during spring fertilization, other nutrients such as sulfur, potassium, and boron are often supplied through fertigation as well. Nitrogen can be supplied through calcium nitrate, potassium nitrate, or ammonium sulfate. If sulfur levels are low in tissue samples, sulfur should be supplied using Epson salt or potassium sulfate. Potassium is supplied through potassium-rich sources such as potassium sulfate and potassium nitrate. If boron was not applied during pre-plant fertigation, 0.125 pound of boron per acre should be applied early in the spring, using Borax or Solubor as source. For more detailed information, please see the Appendix or guidelines from the North Carolina Department of Agriculture & Consumer Services.

Plant tissue sampling. Over-fertilization can cause as much damage as under-fertilization. It is especially important to understand the nitrogen demands of the cultivar you grow. Observe the growth and appearance of your plants in combination with frequent tissue sample analysis over the entire flowering and fruiting season. Plant tissue samples should be taken and be tested every two weeks, starting in early March or April (depending on region). A representative sample of petioles and leaf blades are taken from the newest fully mature leaves. Tissue from different cultivars will need to be kept and analyzed separately. More guidelines on tissue sampling can be found in the Appendix or in guidelines from the North Carolina Department of Agriculture & Consumer Services.

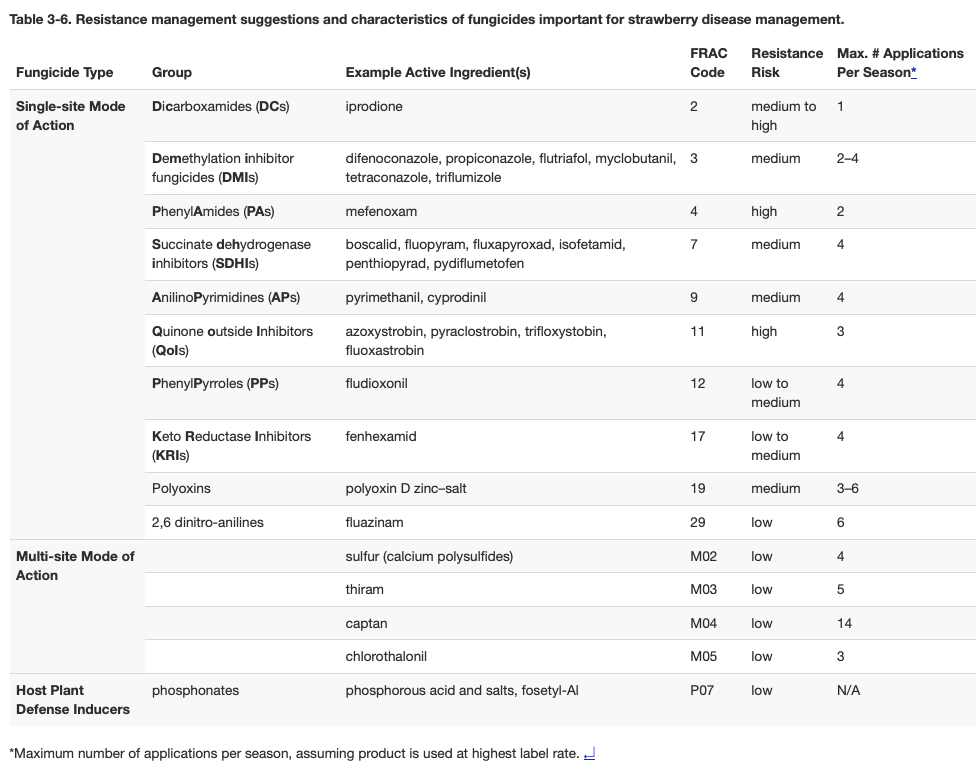

Over time, weeds, mites, insects, and pathogens may develop resistance against pesticides. Furthermore, the continuous application of a single chemical or chemical class aids in the selection of resistant individuals within a pest population. When a pest develops resistance to a particular chemical or chemical class, that chemical or chemical class is no longer an effective management tool for that pest. As such, because pesticides are used heavily in several agricultural systems in the Southeast (including strawberry), pesticide resistance management needs to be practiced every year.

There are several key strategies for pesticide resistance management. The first strategy is rotation, the practice of alternating pesticides so that at each application, a pesticide with a different mode of action is used than the one that was applied in the previous application. The second strategy is to apply pesticide mixtures, either as product premixes or as tank-mixes. Another strategy is to adhere to the seasonal or annual use limitations indicated on product labels for the product itself and, more broadly, for the specific classification group (see below).

In order to effectively use these strategies in a pesticide resistance management program, you must first have some knowledge of pesticides and how they are classified. Numerous pesticides (fungicides, herbicides, insecticides) are available for pest (fungi, weeds, insects) management in strawberries. Each product is composed of one or more active ingredients, as specified in the ingredients section of the label. Different trade or brand name products can have the same active ingredient or related active ingredients. Each pesticide (active ingredient) is known to affect a target pest or group of pests in a specific way, such as the mode of action and target site of the biochemical pathway of the pest.

Pesticides are classified into groups based on their mode of action and target site. These groups are assigned codes, which consist of a number or letter-number combination. The committees responsible for these classifications of fungicides, herbicides, and insecticides are the Fungicide Resistance Action Committee (FRAC), the Insecticide Resistance Action Committee (IRAC) and the Herbicide Resistance Action Committee (HRAC). The codes or groups for the respective pesticides designated by these committees are often referred to as FRAC codes, HRAC codes, and IRAC codes, and are typically printed on the first page of the pesticide label. More information on the committees, including a list of all relevant codes, can be found on their websites.

To effectively practice the strategies for pesticide resistance management, the FRAC, HRAC, or IRAC groups should be considered rather than the product name or active ingredient, depending on which type of pesticide being used (fungicide, herbicide, or insecticide). Additional factors, relevant to fungicides, herbicides, and insecticides, as well as examples, are included in each section below.

Commercial production of high-quality strawberries typically requires an IPM program that includes the use of fungicides. When and how often fungicides need to be applied depends on the fungicide, location, weather, cultivar, and target organism. For example, in some locations and for some cultivars, season-long applications in regular intervals may be necessary to reduce inoculum (pathogen spores) build-up that could otherwise lead to devastating losses when weather conditions favor infection.

The choice of fungicide is important. Some fungicides, namely those with multi-site modes of action, have efficacy against a wide variety of pathogens (broad-spectrum activity, FRAC Mx; Table 3-6) and are not prone to resistance development but often provide insufficient efficacy. Others, namely those with single-site modes of action (FRACx; Table 3-6) have greater specificity and efficacy against certain pathogens, but also have a greater risk for resistance development and must be used in a resistance management program.

Older fungicides, such as sulfur, thiram, captan, and chlorothalonil, have efficacy against a wide variety of plant pathogens. They possess a “multi-site” mode of action, inhibiting multiple biochemical pathways (Table 3-6) in both the pathogen and the plant. As such, these fungicides can be toxic to the pathogen and the plant, and can lead to chemical-induced plant damage (phytotoxicity). To avoid phytotoxicity, these fungicides are designed to stay on the plant surface. It is important to note that if these fungicides are mixed with a product that is designed to penetrate the plant cuticle (such as phosphonates; FRAC P07), multi-site fungicides can become phytotoxic.

Fungicides with single-site modes of action (Table 3-6) only inhibit a single biochemical pathway that often is specific to fungi themselves. That makes them less toxic to the environment, applicator, and consumer, but it also makes them vulnerable to resistance development. For example, a single alteration at the right position of the target gene can make the resulting protein ‘untouchable’ for the fungicide. Table 3-6 shows fungicide types (single-site vs multi-site fungicides), fungicide groups (often indicating their mode of action), and active ingredients of each fungicide group. Multi-site and single-site fungicides are most effective if applied protectively before the fungus has a chance to inhabit the plant. However, single-site fungicides generally do have some systemic activity; they penetrate the plant and halt the fungus after it has already invaded the plant tissue. This curative action has its limitations, however. Most single-site fungicides will only provide effective management within 48 to 72 hours of infection. In areas with heavy clay soil, it may not be possible to move equipment into fields within this timeframe after prolonged rainstorms; preventative applications, therefore, are critical for successful disease management.

Let’s revisit the explanation provided about fungicides at the beginning of the chapter. A grower purchasing a fungicide will receive a product that contains an active ingredient and other inert materials, such as emulsifiers, solvents, carriers, aerosol propellants, fragrances, or dyes. These products possess a brand or trade name. It is important to understand that different trade name products may contain the same fungicide or essentially the same fungicide (different active ingredients with identical mode of action). For example, Merivon and Luna Sensation are different products, but each contains two fungicides with identical modes of action (a mixture of a FRAC 7 and a FRAC 11 fungicide). Resistance management dictates that growers mix or alternate different groups of fungicides. For example, the demethylation inhibitor (DMI) fungicides fenbuconazole and propiconazole are both FRAC 3 fungicides, and the succinate dehydrogenase inhibitors (SDHI) fungicides boscalid and fluopyram are both FRAC 7 fungicides (Table 3-6). Mixing or alternating FRAC 3 and FRAC 7 fungicides is a proper resistance management strategy. Most labels permit two consecutive applications of a product of the same FRAC code before rotating to another.

The most important fungicide resistance management strategy for site-specific fungicides is observing fungicide use limitations. Product manufacturers indicate the maximum number of applications (Table 3-6) or the maximum amount of product permitted per season on the product label. It is critical to understand that the restrictions are meant not for the product itself but for the entire FRAC code. For example, a grower is permitted to use Merivon (a.i. fluxapyroxad + pyraclostrobin) three times per season and Luna Sensation (a.i. fluopyram + trifloxystrobin) four times per season. Both are FRAC 7 + 11 fungicides. In this example, a grower may therefore use EITHER three applications of Merivon and one application of Luna Sensation OR four applications of Luna Sensation per season.

The resistance risk of a fungicide—the likelihood that a fungus will develop resistance to that particular fungicide—is another factor to consider when developing a resistance management program. Mixing a ”high-risk” site-specific fungicide (Table 3-6) with a ”low risk” multi-site fungicide is commonly recommended as a resistance management approach. In such a combination, selection for resistance is minimized if the multi-site fungicide is used at the highest-permitted label rate and the site-specific fungicide is used at the lowest-permitted label rate. As outlined above (in the Merivon and Luna Sensation example), some products contain two fungicides with different modes of action (different FRAC groups); these are premixtures with ”built-in” resistance management. Another example of this is Switch 62.5WG (a.i. cyprodinial + fludioxonil), which contains a FRAC 9 (cyprodinil) and FRAC 12 (fludioxonil) fungicide. The use of premixtures is recommended only if both fungicides are effective against the target organism with no resistance issues.

The choice of which fungicide(s) to incorporate into a resistance management program will also depend on the resistance profile of the pathogens within the area. Fungicide resistance in Colletotrichum spp. and Botrytis cinerea, the pathogens that cause anthracnose fruit rot (AFR) and botrytis fruit rot (BFR), respectively, is widespread, and pathogen resistance to multiple FRAC groups has been reported in some fields. For more information about determining the resistance profile of Anthracnose fruit rot and botrytis fruit rot in your field, see the latest edition of the Southeast Regional Strawberry Integrated Pest Management Guide Focused on Plasticulture Production. Your local Extension agent may also be able to provide information on the specific resistance issues present in your state or geographic area.

Once strawberries are planted, most herbicides can’t be used over the top to manage broad-leaf weeds. Therefore, weed management in beds occurs mainly through the application of fumigants and herbicides prior to planting. Weed management in row middles, however, is possible after planting; we will address herbicide resistance management for weed management in rows middles in this section.

There are two main strategies for herbicide resistance management in row middles. The first strategy is to limit herbicide use throughout the season by following the recommended seasonal use limits as indicated on the label (the maximum number of applications or the maximum amount of product permitted per season). These limits are not for the product itself but for the entire HRAC group. It is also recommended to use the full label rate to manage weeds present in the field. The second key strategy for herbicide resistance management is to practice herbicide rotation, alternating between HRAC codes that control similar weeds. Most labels permit two consecutive applications of a product of the same HRAC code before rotating to another herbicide from a different HRAC code. Scouting your field after any herbicide application is also important to assess if the herbicide was effective.

The most important insecticide and miticide resistance management strategy is to identify your pest. To determine which insects or mites are present in fields, and at what levels, fields must actively be scouted for insect or mite presence or damage. Scouting is essential when determining if an insecticide or miticide application is needed. If insect or mite population thresholds have not been reached, pesticide applications are not recommended and could contribute to an increased risk of resistance development. As previously mentioned, use limitations and insecticide rotation are also important. Additionally, the IRAC has developed resources for each insect and mite that is known to show high resistance. It is critical to review these resources before purchasing and applying insecticides!